Institute Scientists at MRRI, many of whom also hold faculty appointments within the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University, are engaged in important clinical trials testing novel treatment approaches to improve outcomes of patients after stroke, spinal cord injury, phantom pain after limb amputation, and other conditions. In celebration of National Clinical Trials Day on May 20th, MRRI is pleased to highlight current clinical trials and acknowledge the important contributions of volunteers who participate in these trials.

Assessing an Animal-Assisted Treatment Program for Adults with Aphasia: The Persons with Aphasia Training Dogs Program

Aphasia is an acquired language impairment characterized by difficulty with word retrieval, and in some cases, difficulty constructing grammatically complete sentences or with auditory comprehension. People living with aphasia report its consequences reach far beyond linguistic, including loss of identity, engagement, and quality of life. This clinical trial, led by MossRehab Aphasia Center Director Sharon M. Antonucci, PhD, CCC-SLP, will determine the feasibility and potential benefits of the Persons with Aphasia Training Dogs (PATD) Program. Founded in the Life Participation Approach to Aphasia, and working from a strength, rather than deficit, perspective, PATD harnesses the pragmatic skill of persons with aphasia, which is critical to working with dogs, and capitalizes on mechanisms of action for animal-assisted treatment, to ameliorate psychosocial consequences of aphasia. The study will determine whether persons with aphasia can implement positive reinforcement techniques to train dogs in basic obedience skills and define participant characteristics associated with positive response to the intervention. This trial is a crucial first step toward the long-term goal to augment the evidence base with well-specified animal-assisted intervention protocols that target the psychosocial consequences of aphasia.

Criterion-learning Based Naming Treatment in Aphasia

Aphasia most commonly occurs following a stroke. The overarching goal of a clinical trial led by Erica Middleton, PhD, is to develop and test early efficacy, efficiency, and the tolerability of a lexical treatment for aphasia in multiple-session regimens that are comprised of retrieval practice, distributed practice, and training dedicated to the elicitation of correct retrievals. The aim of this work is to add to and refine the evidence base for the implementation and optimization of these elements in the treatment of production and comprehension deficits in aphasia, and make important steps towards an ultimate goal of self-administered lexical treatment grounded in retrieval practice principles to supplement traditional speech-language therapy that is appropriate for People with Aphasia from a broad level of severity of lexical processing deficit in naming and/or comprehension. This project cumulatively builds on prior work to develop a theory of learning for lexical processing impairment in aphasia that aims to ultimately explain why and for whom familiar lexical treatments work, and how to maximize the benefits they confer.

Efficacy and Optimization of Speech Entrainment Practice for People with Aphasia

Research has shown that people with chronic aphasia can benefit from treatment, but significant communication challenges often persist after therapy concludes. A clinical trial led by Marja-Liisa Mailend, PhD, aims to test and develop a promising treatment technique, termed speech entrainment, to enhance treatment outcomes for people with aphasia. Speech entrainment refers to speaking in unison with a model speaker by imitating the model in real time. Research has shown that speech entrainment is a ground-breaking technique for prompting connected speech in people with aphasia. The immediate stimulation effect of speech entrainment is well-documented. The present clinical trial will expand on prior findings to determine the direct effect of speech entrainment practice on independent speech production after the entrainment support is removed. The research team will also identify conditions that enhance treatment benefits and examine participant profiles associated with a positive treatment response. Findings from this study will help inform and enhance rehabilitation for individuals with aphasia.

GetUp&Go: A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intervention to Enhance Physical Activity After TBI

An active lifestyle is known to provide wide-ranging benefits, from lowering the risk of chronic diseases to fostering emotional resilience and mental well-being. For people with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), the challenge of meeting recommended activity levels is compounded by mobility limitations, pain, and the loss of social opportunities. The goal of this clinical trial, led by Amanda Rabinowitz, PhD, is to evaluate GetUp&Go, a program to promote increased physical activity in individuals after TBI. GetUp&Go is a remotely delivered program that includes one-on-one sessions with a therapist and a mobile health application (RehaBot). This clinical trial will determine whether the GetUp&Go program increases physical activity and improves mental and physical health in participants, compared to individuals who are put on a waitlist. The study team will also examine whether continued access to RehaBot helps maintain physical activity gains, as well as participant characteristics associated with treatment response. Their findings will inform the development of interventions to facilitate lasting increases in physical activity after TBI.

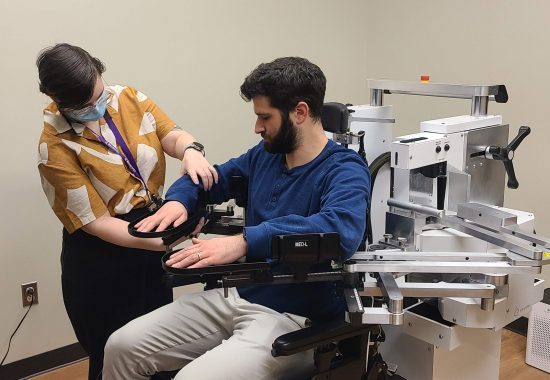

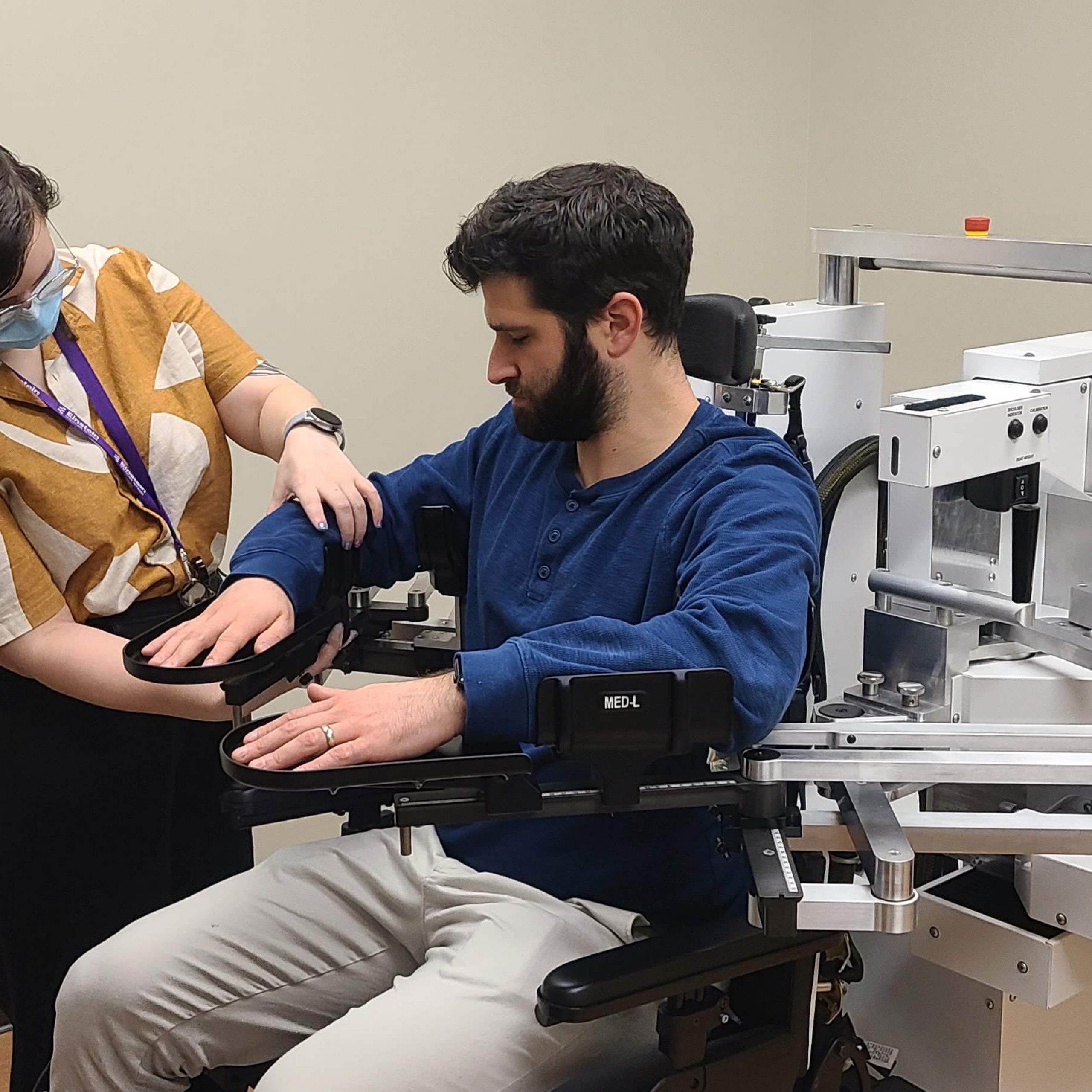

NIBS Therapy in Subacute Spinal Cord Injury (NIBS-SCI1)

Currently, no approved clinical therapies exist for repair of motor pathways following spinal cord injury (SCI) in humans, leaving permanent disability and devastating personal and socioeconomic cost. Promising findings from pre-clinical studies support that non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) may facilitate neural repair following spinal cord injury (SCI). Dylan Edwards, PhD, is leading a clinical trial to begin translating findings from pre-clinical studies to human motor deficits following SCI. This preliminary study will evaluate the effects of a novel non-invasive high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation protocol on arm motor function in people with cervical spinal cord injury. The treatment will involve daily transcranial magnetic stimulation sessions at the inpatient rehabilitation facility. Results from this study will establish the clinical effect size of the intervention, determine the safety and feasibility necessary for a subsequent controlled efficacy trial, and inform preclinical studies for the optimization of dosing.

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation for Post-stroke Motor Recovery (TRANSPORT 2)

Dr. Edwards is also site principal investigator for a multi-site clinical trial led by Wayne Feng, MD (Duke University). This clinical trial aims to determine if non-invasive brain stimulation at different dosage levels, combined with an efficacy-proven rehabilitation therapy, can improve arm function. The stimulation will be delivered via transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), which uses direct currents to stimulate specific parts of the brain affected by stroke. The adjunctive rehabilitation therapy that will be used is called “modified Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy” (mCIMT). During this therapy participants will wear a mitt on the hand of the arm that was not affected by a stroke and will have to use the weaker (more affected) arm. The study will test three different doses of brain stimulation in combination with mCIMT to determine which dose is most effective at improving arm function. Results from this research will help optimize the parameters for non-invasive brain stimulation treatments to enhance motor recovery after stroke.

Virtual Reality Treatment of Phantom Limb Pain

After amputation of an arm or leg, up to 90% of individuals experience a “phantom limb”, a phenomenon characterized by persistent feelings of the missing limb. Many people with a phantom limb experience intense pain in the missing limb that often responds poorly to medications or other interventions. An NIH-funded multi-site clinical trial (NCT05296265) led by Laurel Buxbaum, PsyD, and Branch Coslett, MD (Penn Medicine), is contrasting the efficacy of two virtual reality (VR) treatments for phantom leg pain: an Active VR treatment and a ‘Distractor’ treatment. In the Active VR treatment, participants play a series of novel VR games that provide a realistic rendering of both legs while participants are actively engaged in rewarding VR sports challenges, puzzles, and other immersive activities requiring leg movement. In the Distractor treatment, participants feel passively transported through an immersive VR experience that does not require leg movements. The study is providing important information on how the two types of VR interventions impact pain, psychological health, and quality of life for people with phantom limb pain to inform the optimal clinical treatment of this debilitating condition.