Scientists and staff at Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute (MRRI) have vast experience in working with patients with stroke and other nervous system injuries that can impact decision-making capability. What follows are tips and advice on facilitating appropriate communication based on that experience.

The ethical principle of respect for people as described in the Belmont Report is twofold. It cautions researchers to treat all individuals as autonomous agents throughout the consent process, and it also mandates protections for people with diminished autonomy. Adequately assessing a potential participant’s decision-making capability is crucial for this requirement.

What is Decision-Making Capability, and how does it differ from the legal definition of Competence?

The phrase “decision-making capability” refers to an individual’s ability to make a meaningful, informed decision about a certain task at a point in time. The researcher can assess it with careful consideration during the consent process. Competence is a legal term determined by a court. It can either be a global declaration about a person, or it can be limited to specific domains, such as financial matters, personal care, etc. Decision-making capability regarding research participation must include a person’s ability to:

- Understand the nature of the research procedures, the potential risks and benefits, and the fact that research is voluntary.

- Reason and make a personal judgment about the research in light of their personal priorities, values, and any available alternatives.

- Express choice by communicating their choice (verbally or nonverbally) in a consistent fashion.

- Remember key elements involving the research project for the duration of the consent session.

Preparing to begin the informed consent process, researchers are bound ethically to remember:

- All adults are presumed competent to consent to participation unless there is documented evidence of “decisional impairment.”

- Cognitive impairment may (but does not necessarily) impair decision-making.

- Not all individuals with cognitive impairment have decisional impairment!

The challenge for language researchers is how to tap into an individual’s thought process when they have a diagnosis of aphasia. Aphasia is a language disorder that can impact someone’s ability to understand when listening or reading, and it can inhibit their ability to express their intent fully through speech or in writing to varying degrees. Individuals with aphasia can become prisoners of their native language and may be incorrectly assumed to be incapable of making a decision by virtue of lack of access to language. Researchers should build a ramp to facilitate communication to ultimately determine if it can be determined if a person with aphasia has the capability to make an informed decision.

To determine decisional capability, MRRI scientists recommend the following:

- First, allow ample time for the consent process. Some participants may need more than one session. Be prepared to continue the “process” over several sessions if necessary. The participant should never feel rushed.

- Encourage the participant to bring a family member or trusted friend with them; not to make the decision for them, but to act as a second pair of ears or a source of comfort.

- Use outside enhancements to the printed consent form to facilitate understanding of concepts. While it may not be possible to modify all parts of a consent form to accommodate a 5th grade reading level for better health literacy, effort should be dedicated to parsing longer sentences into chunks, rephrasing vocabulary as necessary, and adding pictures to illustrate a task.

- Acknowledge the participant’s capability nonverbally through welcoming posture and eye contact; and frequently verbalize support (e.g. “I know you know it”) to dispel fears they may have about trying to communicate.

- Researchers should acknowledge frustrations and attribute breakdowns to their own limitations as a listener. For example, “Gee, I’m having a lot of trouble today, but I’m going to do my best to understand what you have to say.”

- Openly explain the need to speak to someone else if critical information is needed. A researcher might say, “I think we need to bring your wife in so I can make sure I understand whether you can have the MRI.”

- Throughout the consent process, ask predetermined questions to elicit responses to specific concepts that need to be communicated, but always pay close attention to the participant’s nonverbal reactions at other junctures to see if there is need for additional intervening questions. Ask the comprehension questions that pertain to a specific topic soon after that topic is discussed to aid understanding.

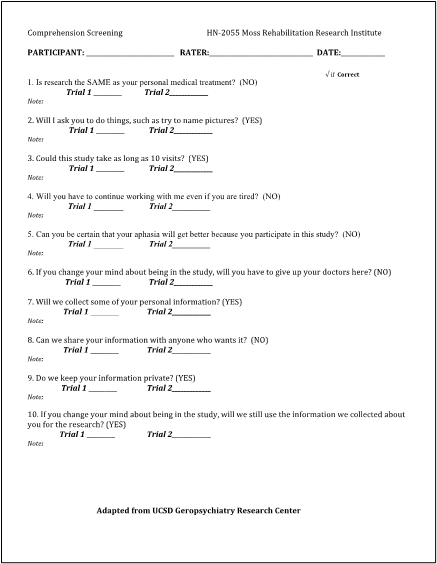

This is a comprehensive questionnaire used by the Middleton Language and Learning lab, in which people with aphasia undergo language assessments.

8. Use the techniques of Supported Conversation for Adults with Aphasia (SCATM) to frame the interaction with the participant during these consent questions:

Reveal Competence:

- Is the researcher’s message getting IN?

- Judge how much support is needed and overcome the barrier by adding meaning in layers.

Nonverbal support:

a. First, add gesture. These are meaningful, slightly exaggerated movements used to emphasize or clarify. For example, a researcher could hold up 10 fingers to emphasize 10 visits.

b. Supplement with writing. Make sure to have clear and visible appropriate “key” words.

c. Picture Resources or drawings: These should be used when necessary (ask yourself if something simpler would suffice). However, they may be helpful for explaining tasks that a participant would be asked to do in a research study. For instance, a scientist could explain how one task in a study will involve a participant saying the names of objects in pictures. They could then demonstrate by pointing at a picture and saying the name (e.g. “It’s a cab”.)

Verbal support:

a. Start with short simple sentences.

b. Use redundancy.

c. Be prepared to repeat, rephrase, expand, and recap to verify understanding.

Participant: “one day?”

Researcher: “yes, you start with one day. Then 9 more days (while pointing on a calendar). You could come here a total of 10 days. Was that your question?”

- Look for the person’s response to communicative cues. Researchers can assess whether a participant is interacting in dynamic and meaningful ways, or if instead there is a lack of expression or constant nodding yes.

- Is the participant’s message getting OUT?

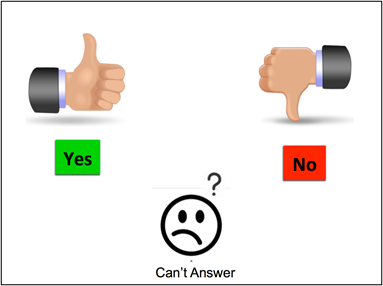

Determine if the person has a nonverbal way to answer questions.

a. Gesture: pointing, thumbs up/down

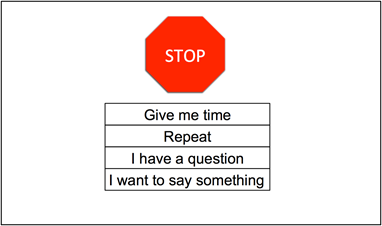

b. Evaluate whether the person has a way to control the conversation flow.

Encourage writing (make sure there is paper and pen) and/or provide written key words for pointing with use of yes/no and fixed choice questions.

d. Actively suggest that the participant give you a clue.

- Acknowledge competence throughout interactions.

a. Verify each chunk of information to ensure that the conversation is on track from the perspective of the person with communication challenges. Researchers should always check to make sure they understood what the potential participant intended to say.

b. Summarize slowly, reflect, and expand: “So let’s see if I’ve got this right” This can help to catch inconsistent yes/no responses and hone in on misconceptions. It gives both the researcher and the participant a chance to catch an inaccurate assumption.

Communication may not always be successful the first time. If a potential participant doesn’t understand something, a researcher should be prepared to rephrase what they said. If a researcher doesn’t understand a potential participant’s response, they should ask again to make sure.

While this post focuses primarily on how to proceed with the consent process in order to determine a person’s decisional capability, the principles of Supported conversation for Adults with Aphasia (SCATM) can and should be used from the very first interaction in recruitment either via phone or in person throughout the length of the study—

well beyond obtaining consent. Confirming that your participant understands all directions and has a way to answer your study questions adequately helps to ensure valid data collection.

Belmont report (1979) – Issued by the National Commission for the Protection Of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html

Kagan, A., Black, S.E., Duchan, F.J., Simmons-Mackie, N. & Square, P. (2001). Supported Conversation for Adults with Aphasia (SCA™), Aphasia Institute, www.aphasia.ca

64 comment on “Facilitating Informed Consent for People with Aphasia and Cognitive Impairment: Breaking through Communication Barriers in the Language and Learning Lab”