What’s the word? Those tip-of-the-tongue moments, when a word is seemingly right there but just out of reach, can temporarily hinder our ability to communicate effectively. Everyone experiences word-finding challenges (called anomia) from time to time. However, for people who have aphasia, an acquired language disorder following stroke or brain injury, these word-finding challenges can be very frequent and disruptive, causing problems for everyday communication needs. Verbs present a particular challenge for the majority of people with aphasia. Verbs are vital because we need them to communicate about actions and events, and they are central to sentence structure and conveying relationships between subjects and objects. Without using verbs, language can sound telegraphic or robotic, and it becomes very hard to get a point across.

Gestures can help people retrieve words when they get stuck. Using a gesture to pantomime an action can convey a speaker’s intended message to others, and it can furthermore help the person produce the verb they want to say. Unfortunately, producing gestures can also be impaired following stroke, and many patients who have aphasia also have limb apraxia, a disorder that impairs skilled action and gesture production.

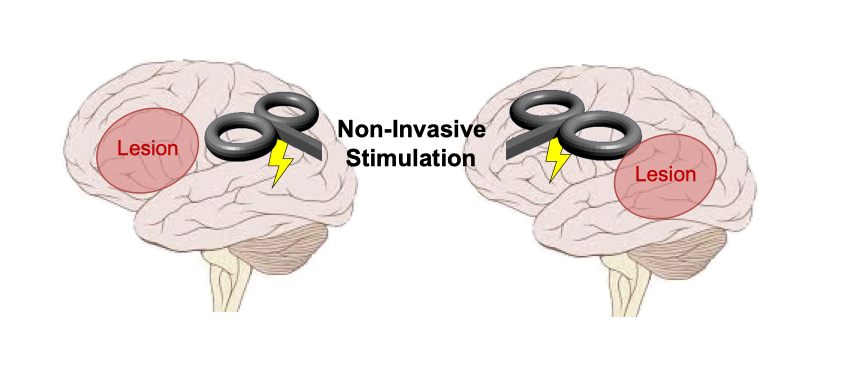

However, it is possible that simply watching someone else produce a gesture may help adults living with stroke to get those words off the tip of their tongues. This is possible when an observed gesture and intended verb share meaning, or semantics. Semantic knowledge consists of everything we know about the world, and it is stored in long-term memory. Semantics are distributed in a network of regions across the brain and can therefore be resilient to damage. Neurorehabilitation treatments that enhance semantic activation may therefore benefit many patients with different patterns of brain damage. Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute (MRRI) and University of Pennsylvania researchers Haley Dresang, PhD, Laurel Buxbaum, PsyD, and Roy Hamilton, MD, MS, are combining gesture observation with non-invasive brain stimulation to investigate whether enhanced activation of action knowledge (semantics) can facilitate verb production in patients with aphasia. This is the first study to implement a specific type of excitatory stimulation – intermittent theta-burst stimulation – on verb-production impairments, and also the first to combine brain stimulation with gesture-observation cues in aphasia. First, this research examines whether passive observation of gestures can help patients produce verbs. Second, this research compares the benefit of gestures on verb production in patients who have had a stroke that damaged the left anterior versus the left posterior parts of the brain. Third, Dr. Dresang and colleagues are also investigating whether applying non-invasive brain stimulation to increase activation in intact nodes of the semantic neural network will enhance the benefits that observing gestures may have on verb production. The researchers will apply a magnetic current that amplifies the activity of neurons in brain regions important for semantic processing, and they will assess whether patients are able to successfully name more verbs based on observed gestures while receiving this brain stimulation. This study will begin recruiting participants later this summer. This research advances scientific understanding of how the brain functions following injury. Furthermore, this work seeks to create a novel neurorehabilitation approach that will improve treatment success for a variety of stroke patients with language and/or motor impairments.

2 comment on “Using Gestures and Brain Stimulation to Enhance Language in People with Stroke”