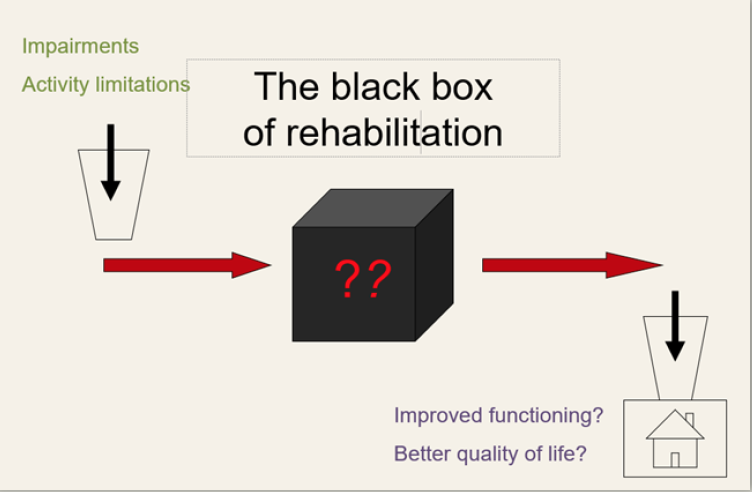

Rehabilitation has been described as a “black box”. We can specify and measure a number of patient features at the time of rehabilitation treatment that predict functional improvement (e.g., demographics, measures of severity). We can also specify and measure the outcomes that rehabilitation treatments hope to achieve. However, we have no shared language for specifying and measuring the rehabilitation treatments themselves. In the case of drug treatments, this is straightforward: specifying the treatment amounts to naming the active chemical ingredient and the dose. In contrast, most rehabilitation treatments involve some form of interaction between clinician and patient/client. What “active ingredients” are delivered during these interactions and in what “dose”?

Until now, we have had only very crude ways of defining rehabilitation treatments. Sometimes we talk about exposure to a particular kind of facility (12 days of inpatient rehabilitation) or discipline (3 one-hour sessions of PT per week). In some cases, we name treatments by the problem they address (gait training, memory remediation). Neither of these approaches is sufficient. Two clinicians providing “gait training” might be pursuing very different training regimens, and we cannot assume that either everything or nothing a PT does in a session is “effective”; we need to know what they did. The current state of rehabilitation treatment specification makes it hard to:

- replicate treatment research (replication means delivering the same active ingredients in a new study)

- disseminate effective treatments or ensure clinicians are delivering them correctly (i.e. what would a supervisor look for to ensure that the active ingredients are being delivered?)

- synthesize evidence across studies (i.e. should we combine studies of memory notebooks, mnemonic strategies, and reminder technology in a meta-analysis because they are all “memory remediation”?)

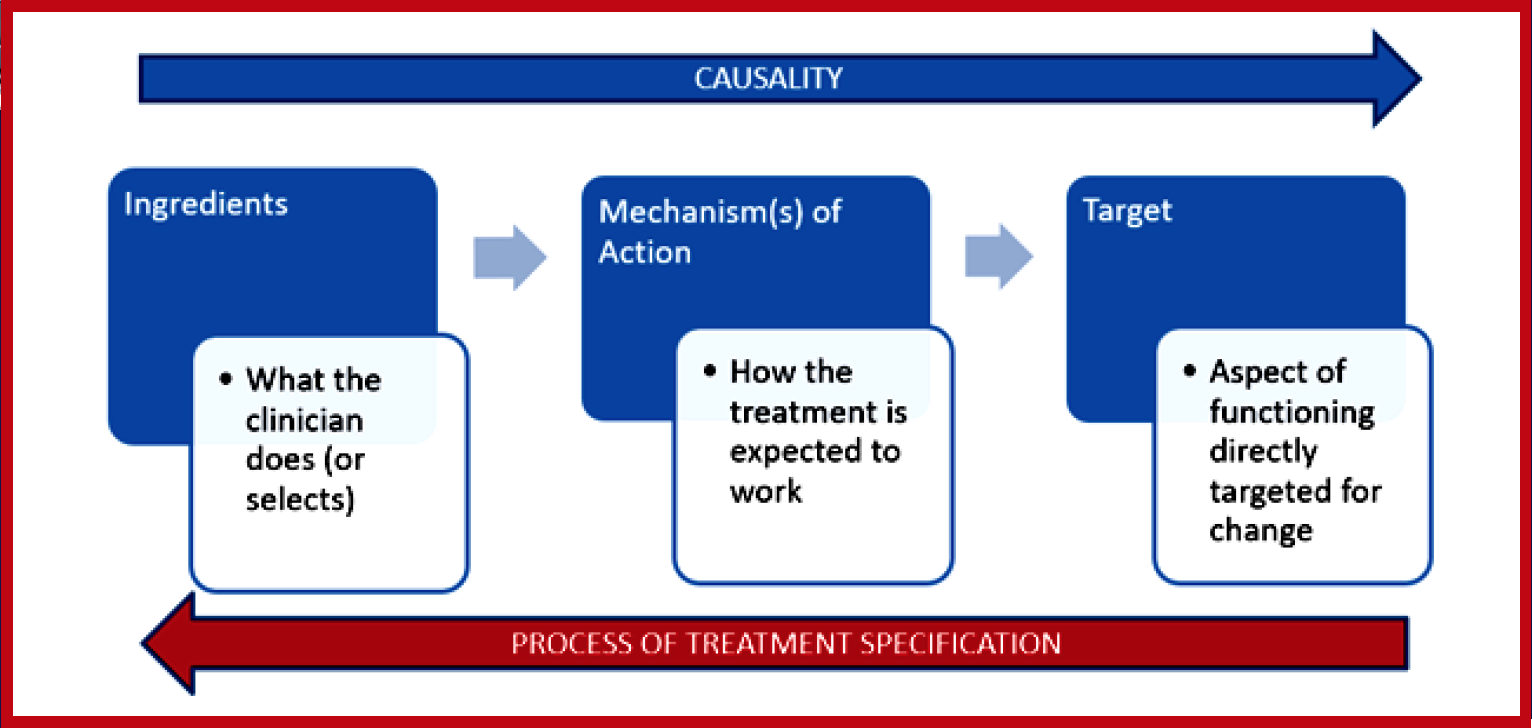

For more than 10 years, a group of rehabilitation scientists and clinicians, at MRRI and elsewhere, have been working to develop a standardized system for specifying any and all rehabilitation treatments. We have established already that there is more than one way to do this, so the question is, Of the many ways that we could define and categorize rehabilitation treatments, which would be most useful in advancing science and practice? We argue for a treatment specification system based on the treatment’s known or hypothesized active ingredients. In this way, testing the efficacy of a treatment called “Treatment X”, is a test of the efficacy of a replicable set of ingredients as well as a test of the theory that those ingredients should produce clinical change: the treatment theory.

With an initial grant from NIDILRR (PI: Marcel Dijkers, PhD), the group developed this conceptual framework, the Rehabilitation Treatment Specification System (RTSS). With subsequent PCORI funding (PI: John Whyte, MD, PhD), these concepts were elaborated into a procedural process in the Manual for Rehabilitation Treatment Specification and described in a set of interrelated articles. The RTSS and its manual have now found a home at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM)’s Rehabilitation Treatment Specification Networking Group (RTS-NG), which serves as an organizing hub for the many clinicians and researchers around the world that seek to implement the RTSS framework into their work.

Anticipated benefits of the RTSS have been framed around three areas of rehabilitation: research, clinical practice, and education. We believe that use of the RTSS in the design, replication, and reporting of research will improve the development of treatments. It will encourage more systematic descriptions of the target of the proposed intervention – the direct, functional change that it is designed to cause; as well as the treatment ingredients – what is required in enacting the treatment in order to bring about the desired change in the target. Implementation of research into practice will also benefit, as providing more explicit descriptions of treatments and having a clearer understanding of the relevant components will assist the clinician in using these treatments with their individual patients.

Within clinical practice, use of the RTSS is also expected to enhance clinical reasoning, as the system facilitates consideration of the theoretical mechanisms that underlie rehabilitation treatments. The RTSS recognizes that, for example, many treatments across diverse rehabilitation settings rely on the mechanism that when a skill is practiced in the right way, that skill is improved upon. Whether the skill involved is reaching, articulating a word, or the act of walking, the RTSS directs considerations such as:

- What are the important ingredients involved in the practice of that skill?

- In what way is that skill desired to be changed?

- Is it conceptually plausible? that the ingredients used will make the desired change?

- What is the scope of the desired change in terms of generalizability, and will the ingredients support that?

The RTSS also has benefits in clinical education and training. Communication of treatments, both within and across disciplines, is enhanced through not only better identification of these essential elements of treatments as mentioned above, but also by providing a common language and systematic framework to describe treatments.

The RTSS has been used at MossRehab by groups of clinicians, including residents and fellows in MossRehab’s advanced training programs for occupational and physical therapists. While many trainees endorsed the benefits of more thoughtful consideration of both ingredients and targets of treatments, they also encountered some challenges in adopting this new system.

One common issue among clinicians was difficulty learning new RTSS terminology and needing time to “convert” daily documentation to align with RTSS guidelines. Not surprisingly, the extra time is a considerable barrier to clinical implementation. However, over time, we think that barrier will be reduced because academicians are interested in using the RTSS to teach methods of therapy delivery to their students. This conceptual framework can help students link clinical theory to specific actions (ingredients) by facilitating discussion regarding the treatment targets and details of intervention delivery. Active learning experiences during case studies and client simulations can engender habits of clearly describing treatments and evaluating the fit between ingredients and targets. The RTSS provides the structure and terminology to depict how the ingredients can be modified, based on patient performance. As such, students fortified with the RTSS will be better equipped to examine and understand the process of therapeutic change. Further, on a larger scale, colleges with allied health programs now have a structure that crosses multiple disciplines and can naturally enhance their inter-disciplinary education experiences.

These ongoing efforts in education, clinical practice, and research support our hope that the RTSS can be unifying for the field of rehabilitation.

For more information, please see these additional articles on the RTSS:

11 comment on “Development of the Rehabilitation Treatment Specification System”